Coastal Sediment

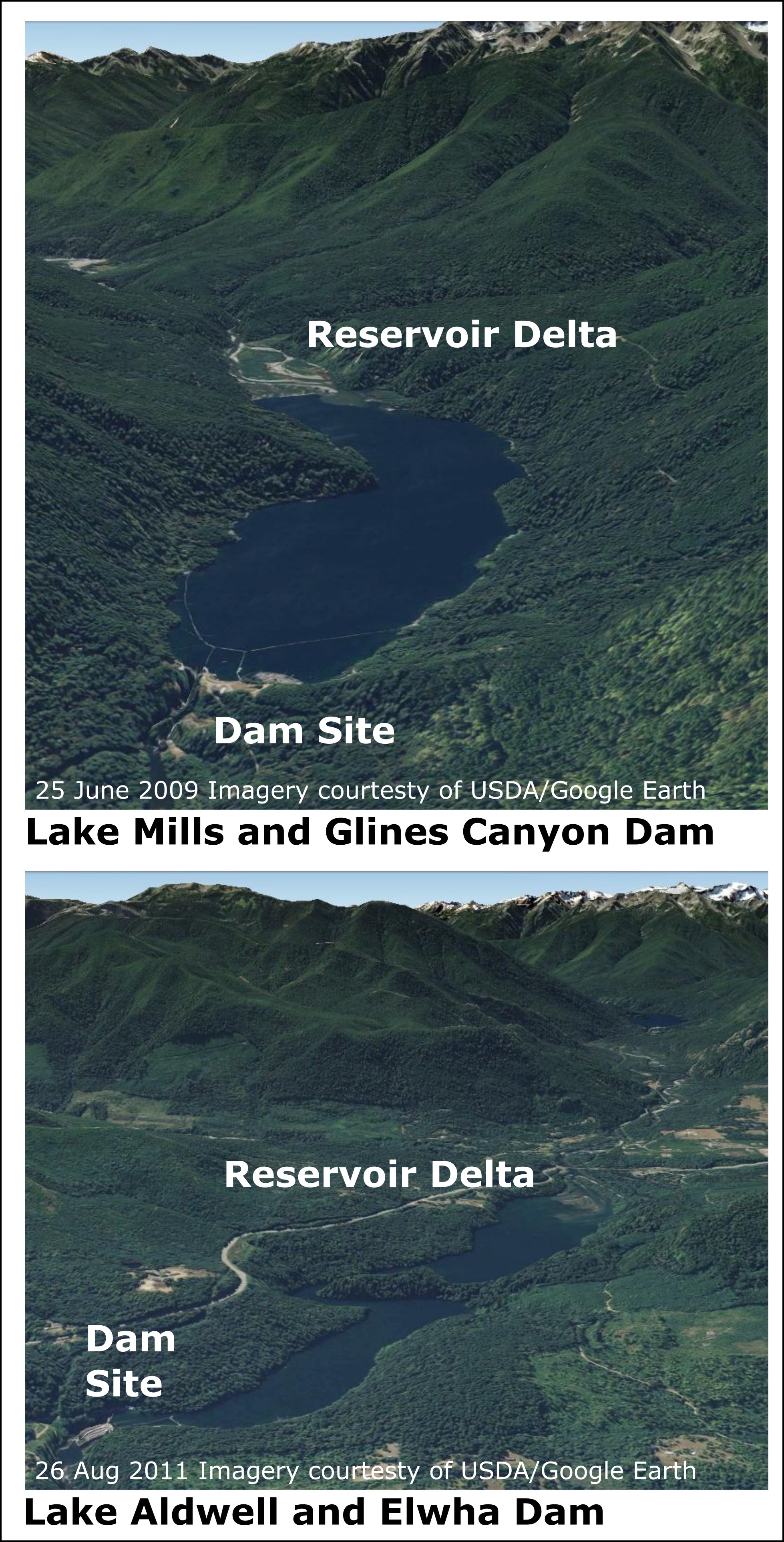

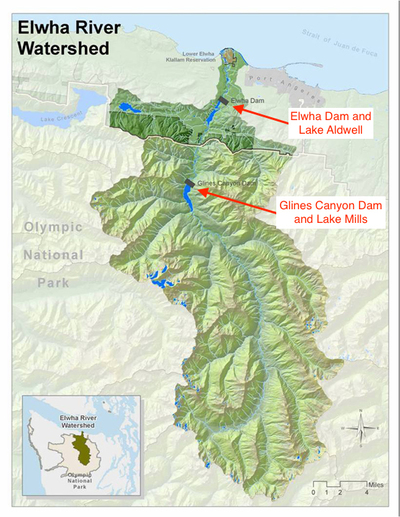

After nearly 100 years with two large dams in place, by the time the Elwha River dam removals began in 2011 the structures had trapped roughly 30 million tonnes of sediment behind their walls. That’s enough to fill Seattle’s CenturyLink Field nine times over! This massive deposit of sediment was composed of mud, sand and gravel. It was primarily stored in two lake deltas, one in each reservoir.

After nearly 100 years with two large dams in place, by the time the Elwha River dam removals began in 2011 the structures had trapped roughly 30 million tonnes of sediment behind their walls. That’s enough to fill Seattle’s CenturyLink Field nine times over! This massive deposit of sediment was composed of mud, sand and gravel. It was primarily stored in two lake deltas, one in each reservoir.

The Elwha River is a relatively steep coastal watershed, dropping roughly 6,000 feet in just 50 miles. So when the dams were removed from the watershed, it didn’t take long for sediments trapped in the river’s reservoirs to move downstream and make their way to the ocean waters of the Strait of Juan de Fuca.

The first pulse of sediment to make it to the Strait of Juan de Fuca was mostly mud, which formed a persistent sediment plume and started a cascade of ecological changes in the nearshore ecosystem as the concentrated sediment shaded the seafloor (similar to how a dust storm or thick clouds obscures the sun).

A little over a year after dam removal started, in November 2012 the first massive pulse of sand and gravel made it to the coast, burying a small area of seafloor near the river mouth. Over the next three years the sediment continued to pulse out of the river mouth, building a series of bars and estuarine lagoons, burying small areas of seafloor under sand or mud, and reducing the amount of light making it to the seafloor. Read the next section, “Habitat in Transition,” to learn more about how these sediment pulses changed the nearshore environment.